Why Breaking Bad Refused to Be a Redemption Story

Examining the Show’s Unapologetic Approach

Breaking Bad chose not to be a redemption story because its central character, Walter White, fully embraced his darker instincts rather than seeking forgiveness or change. From its earliest episodes, the series followed Walt’s steady transformation from an ordinary chemistry teacher into a calculating criminal, deliberately avoiding the familiar path of moral rehabilitation.

The show’s creators were intentional about showing the consequences of Walt’s decisions, resisting the urge to offer him an escape or absolution. Each choice Walt made took him further from redemption, challenging viewers to confront the reality that some characters do not seek or deserve it.

By refusing to frame Walt’s story around redemption, Breaking Bad set itself apart from many television dramas. This narrative decision invites audiences to reflect on the meaning of consequence, personal responsibility, and the boundaries of sympathy.

Breaking Bad’s Narrative Approach

Breaking Bad was deliberately constructed to challenge the conventions of antihero storytelling. The series embraced difficult questions about morality, transformation, and audience expectations without offering easy resolutions.

Series Creation and Thematic Intent

Vince Gilligan, the creator of Breaking Bad, often described his goal as turning Mr. Chips into Scarface. This vision shaped the show’s narrative from its premiere on AMC in 2008 through its series finale.

Rather than promising redemption for its characters, the series focused on the consequences of moral choices. Walter White’s journey emphasized personal responsibility and the cumulative effects of small compromises. Gilligan wanted viewers to examine whether some choices could ever be undone, and whether true atonement was possible for certain actions.

The show’s meticulous plotting and character arcs reinforced this intent. Walter’s transformation was gradual, highlighting the difficulty—and sometimes impossibility—of reversing a destructive path.

Distinguishing Breaking Bad From Traditional Redemption Arcs

Unlike many dramas that encourage viewers to root for antiheroes to find redemption, Breaking Bad refused to reassure its audience with hope for Walter’s salvation. Most television narratives that focus on crime or morally ambiguous characters, such as The Sopranos, eventually explore efforts at atonement or moral improvement.

Breaking Bad stands out by making it clear that its protagonist moves further away from redemption as the series progresses. In Jesse Pinkman’s story, attempts at making amends are consistently complicated by circumstance and personal flaws.

The show directly confronted the desire to forgive main characters. Instead of offering redemption, it emphasized the lasting damage caused by their decisions. This narrative choice set the series apart from more comforting storytelling traditions.

Avoiding Predictable Storytelling

Breaking Bad disrupted viewer expectations by refusing standard narrative formulas, including the redemptive arc. Gilligan and his writing team opted for authenticity and escalation over melodrama, focusing sharply on the logical outcomes of character choices.

Dramatic tension developed from credible reactions and realistic consequences rather than narrative convenience. For example, Walter’s lies and decisions frequently led to irreversible consequences, making the story more suspenseful and hard to predict.

The performances, especially by Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul, grounded the story in realism and complexity. The result was a series that maintained unpredictability by consistently denying viewers the comfort of redemption.

Walter White’s Transformation

Walter White's journey in AMC's Breaking Bad charts the evolution of a man who begins as a struggling chemistry teacher and gradually becomes the infamous Heisenberg. His transformation exposes the interplay of scientific expertise, shifting moral boundaries, and the impact of personal ego and pride on one's fate.

From Chemistry Teacher to Heisenberg

Walter White starts as a high school chemistry teacher in Albuquerque, facing financial difficulty and a cancer diagnosis. His knowledge of chemistry provides a way into the methamphetamine trade, where he initially claims his actions are for his family's security.

As he uses his scientific skills to build a potent product, Walter adapts quickly to the criminal world. He adopts the alias "Heisenberg," symbolizing his shift from a mild-mannered educator to a calculated drug manufacturer.

Key transformation markers:

Breaking bad after cancer diagnosis

Use of chemistry as a criminal tool

Gradual increase in calculated violence and manipulation

By the time he fully becomes Heisenberg, his identity as a teacher is virtually erased, replaced by someone entirely shaped by the demands and dangers of the drug trade.

Moral Ambiguity and Antihero Evolution

Walter does not become a villain overnight. His transformation involves a series of ethically questionable decisions—stealing, lying, violence—that advance his goals but erode his humanity. He convinces himself that the ends justify the means, but these rationalizations weaken over time.

His moral ambiguity blurs the line between victim and perpetrator. While he claims necessity and family as motives, he repeatedly chooses actions that harm others for self-preservation or gain.

This evolution positions Walter as an antihero. He elicits both sympathy and condemnation as viewers witness the consequences of each choice, resulting in a complex, psychologically intense character whose ethics are constantly shifting.

The Role of Ego and Pride

Ego and pride are central to Walter White’s transformation. Early in the series, his sense of inferiority and frustration about his underappreciated intellect fuel his resentment. As Heisenberg, he craves recognition and respect, moving far beyond financial motives.

Walter’s hubris grows with his success in the drug business. He rejects opportunities to walk away and escalates dangerous situations to assert dominance.

Key examples of pride driving his choices:

Refusing financial help from friends

Demanding respect from criminal rivals

Justifying increasingly violent acts

Over time, Walter’s decisions become more about personal legacy than family, illustrating how ego and pride override initial intentions and drive his downfall.

Why Redemption Was Refused

"Breaking Bad" shifts away from traditional paths of redemption, focusing instead on the weight of personal choices and their consequences. The show’s portrayal of Walter White’s journey centers on actions, motivations, and the lasting impact of his decisions, rather than offering him absolution.

Consequences Over Catharsis

The writers emphasize that actions have lasting effects that cannot be easily erased. Walter White’s decisions, from manufacturing meth to manipulating those around him, destroy lives and leave deep scars. Rather than seeking or earning forgiveness, he faces the reality of his choices squarely.

Key episodes highlight how Walter’s pursuit of pride outweighs any genuine remorse. When given opportunities to admit guilt or make amends, he rarely does so without ulterior motive. The show avoids dramatic last-minute redemption in favor of showing that some damage cannot be undone.

By refusing the emotional release that comes with redemption, "Breaking Bad" forces viewers to confront the full weight of Walter’s wrongdoing. The series treats the consequences as ongoing, not neatly resolved or redeemed by final acts.

Exploring Sin and Responsibility

Walter’s story is shaped by themes of sin and personal responsibility. Instead of framing him as a tragic hero in need of saving, the narrative holds him accountable for each choice and its moral cost. Guilt is portrayed as a natural result rather than a path back to grace.

The show repeatedly places judgment in the hands of characters who suffer from Walter’s actions, making clear that redemption cannot simply be claimed. Responsibility is not just about feeling bad but acknowledging harm and enduring its fallout.

By the finale, Walter recognizes his motives were driven by ego rather than necessity or love. This admission underscores that redemption requires more than confession—it demands sincere change, which he never truly pursues. The series ultimately rejects a narrative of spiritual or moral restoration for Walter, insisting that not all stories conclude with forgiveness.

Key Relationships and The Absence of Forgiveness

Breaking Bad’s refusal to deliver redemption is most visible in its critical relationships. Failures in trust, compassion, and forgiveness shape the destinies of each major character as loyalty erodes.

Family, Love, and Eroded Trust

Walter White’s drive begins with a desire to support his family, but his actions undermine true connection. His secrecy destroys intimacy with Skyler and distances him from his son, Walt Jr. Skyler shifts from supportive spouse to a partner who resents and fears Walt's choices, challenging the idea that family bonds are unbreakable.

The show's depiction of love is often transactional or manipulative. Walt repeatedly justifies his criminal behavior as an act of love, even while endangering his family. In these moments, attempts at forgiveness are rare—betrayals are remembered, not excused.

Across the White family, suspicion and resentment quietly replace affection. Trust, once broken, is never fully restored, and apologies come too late or are never offered at all. No character achieves real reconciliation, highlighting the show’s bleak take on personal relationships.

Conflict With Jesse Pinkman

Walt’s relationship with Jesse is marked by cycles of manipulation, loyalty, and betrayal. Walt often treats Jesse as both surrogate son and expendable partner, leveraging Jesse’s vulnerabilities to achieve his own goals. Their dynamic is built on a foundation of guilt and necessity rather than forgiveness.

Jesse seeks recognition and compassion from Walt but is repeatedly let down. After key betrayals—including Brock’s poisoning—Jesse finds it impossible to forgive, leading to irreversible separation. Their partnership, once essential for survival, becomes toxic, with reconciliation always out of reach.

Jesse’s struggle for freedom from Walt encapsulates the show’s theme: broken trust cannot be mended. Instead of mutual understanding or forgiveness, the relationship is defined by manipulation, regret, and unresolved anger.

Skyler, Hank, and The DEA

Skyler’s involvement in Walt’s crimes places her under immense psychological strain. Her relationship with Hank, her brother-in-law and a DEA agent, is complex; she hides the truth to protect herself and her children, even as guilt grows. The family is torn between self-preservation and honesty.

Hank’s pursuit of Heisenberg becomes personal as he realizes Walt's true identity. When the truth emerges, any possibility of familial loyalty collapses. Neither forgiveness nor compromise is possible—Skyler and Hank are pitted against each other, forced into opposing sides.

The DEA’s investigations further isolate Skyler, whose actions cement her in a world without absolution. The hostile standoff between Hank and Walt signals the end of family unity, demonstrating that once trust is violated on this scale, forgiveness is not an option.

Power, Money, and Empire Building

Walter White’s descent is driven by more than survival or family. His decisions center on ambition, ego, and the pursuit of dominance within the unforgiving world of the meth business.

Greed and the Need for Control

Walter’s transformation from teacher to drug lord is anchored in greed and a desire for control. Early in the series, he rejects financial help from old friends, despite their genuine offers, because accepting would compromise his pride.

He wants to be seen as the provider and architect of his own fortune. Control, not just money, motivates him. The series repeatedly shows Walt making choices that protect his authority within his criminal operation, even if it means risking everything.

For Walt, the "empire business" becomes the end goal. Making and protecting vast amounts of cash is only meaningful when he commands the power behind it. This unchecked need for control steadily erodes his morality.

The Meth Business and Drug Money

Walt’s entry into meth production quickly shifts from desperation to profit-driven enterprise. As his operation expands, he amasses enormous stacks of cash, which he often cannot even launder or spend safely.

Much of the drama centers on the physical presence of money. Scenes of cash-filled storage units highlight the scale of his empire, but also the futility—most of it sits unused, attracting danger and suspicion.

The distinction between providing for his family and accumulating for the sake of accumulation begins to blur. Walt’s focus on the business overshadows any practical need for money. Power and notoriety within the meth trade become their own rewards.

Criminal Entanglements

Building and defending an illegal empire inevitably ties Walt to violence, betrayal, and manipulation. His rise forces him into alliances with cartel members, criminals like Gustavo Fring, and ultimately with men who threaten his safety and autonomy.

Each step towards consolidating his power exposes him to new threats. Attempts to control the criminal world lead to increasing bloodshed and paranoia. Walt’s pursuit of the "empire business" brings about a cycle of escalation: each gain is met with higher risk and deeper corruption.

This entwinement with criminal networks illustrates that success in the drug trade is inseparable from moral decline and legal peril. Walt's empire is maintained not just with money, but with fear and ruthless choices.

Morality, Consequences, and Downfall

Breaking Bad centers its narrative on the choices characters make and the chain of consequences that follow. The story consistently examines the high costs of unchecked ambition, personal temptations, and the inevitable downfall that arises from moral ambiguity.

Major Deaths and The Cost of Ambition

Deaths in Breaking Bad are rarely random. Each major character’s execution or demise often stems directly from choices made in pursuit of power or money.

Walter White’s actions lead to the deaths of Gus Fring, Mike Ehrmantraut, and even his brother-in-law, Hank Schrader. Each death is a product of costly ambitions and ever-escalating risks. The series does not shy away from showing the aftermath—families are left devastated, and power structures collapse.

Skyler and Jesse suffer indirect but severe losses. Jesse’s relationships and sense of self are destroyed by his involvement in Walter’s world. The moral ambiguity in every decision is stark; loyalty or success never come without heavy personal costs.

Addiction, Temptation, and Downfall

Temptation is a persistent force for multiple characters. Walter grows addicted not only to money, but to the power and control his new life gives him.

Jesse battles substance addiction, but he is also tempted by the hope of redemption and moral clarity, which remains elusive. The lure of easy money pulls both down paths they cannot escape, reinforcing that temptation is not limited to drugs but extends to risk, ego, and violence.

Their downfalls are gradual and often self-inflicted. Walter transforms from sympathetic teacher to morally ambiguous criminal, demonstrating that small temptations can lead to irreversible ruin. The consequences are relentless, highlighting the escalating cost of giving in to temptation, whether chemical or psychological.

Critical Episodes and Plot Mechanisms

Several pivotal episodes and narrative choices drove Breaking Bad’s refusal to deliver a simple redemption arc. These moments focused on consequence, moral reckoning, and the gradual stripping away of illusions that redemption was ever the true endgame for the main character.

Ozymandias and the Collapse

"Ozymandias," often cited as one of the finest episodes in television, marks the irreversible downfall of Walter White. After a series of devastating choices, Walt loses his fortune, family, and authority. The episode makes use of rapidly escalating consequences, highlighting the irrevocable damage caused by his ambition.

Key moments include the confrontation in the desert where Hank is killed, shattering any last vestiges of hope for Walt’s redemption. The survival of his family is no longer guaranteed, and relationships break beyond repair. The episode's title itself—an allusion to Percy Shelley's poem about ruined empires—reinforces the theme of unavoidable decay and failure.

Breaking Bad uses "Ozymandias" as a focal point where consequences finally catch up, signaling a clear rejection of redemptive closure.

Felina: The Series Finale

The series finale, "Felina," avoids a feel-good ending in favor of reckoning and resolution. Walter returns to Albuquerque to tie up loose ends, but the episode does not frame his actions as redemptive. His confession to Skyler is honest, admitting he acted for himself, not the family.

The final events involve Walt orchestrating revenge against his former partners and ensuring a portion of his money reaches his son. However, his fate is sealed—Walt dies alone, and his attempts at control come too late to save those he hurt. The tone of "Felina" is somber and direct, choosing closure over false amends.

This approach emphasizes consequences and ensures the ending remains balanced, steering away from absolution.

Notable Plot Twists

Key plot twists throughout Season 5 underscore the series’ anti-redemptive stance. The poisoning of Brock, the train heist, and the orchestrated demise of rival gangs show Walt’s continual descent, making it clear that moral turnaround is never in play.

These pivotal twists strip characters of easy answers and undermine the notion of a last-minute rescue or reset. Each surprise escalates stakes and hardens the narrative approach, culminating in irreversible decisions.

Table: Key Twists and Their Effects

Twist Consequence Poisoning Brock Loss of Jesse’s trust Train Heist Further moral degradation Killing Mike Ehrmantraut Cuts ties with possible allies Betrayal of Todd's gang Final self-destruction

By refusing deus ex machina solutions or convenient reversals, these mechanisms reinforce the show’s clear departure from a redemptive storyline.

Major Characters and Their Arcs

Breaking Bad presents layered character transformations that highlight themes of moral decay, justice, self-preservation, and the interplay of criminal power. Each figure’s choices reveal the series’ unwillingness to deliver simple redemption or moral closure.

Jesse’s Moral Conflict

Jesse Pinkman undergoes a series of moral struggles, marked by guilt over his actions and the harm he causes to others. Despite numerous attempts to make amends—such as trying to leave the drug trade or protect children—he rarely finds peace.

Jesse’s relationship with Walter White repeatedly drags him back into violence and deceit. His conscience is clear in moments where most other characters are self-serving. Yet, the world he inhabits offers no easy path to forgiveness or atonement.

Jesse’s arc explores the pain of living with irreversible choices. Despite a yearning for redemption, the show frames his suffering as ongoing rather than fully resolved.

Hank and The Pursuit of Justice

Hank Schrader operates as a counterpoint to the criminal world, embodying law enforcement’s perseverance and fallibility. His investigations into the drug trade stem from personal dedication rather than vengeance.

Hank’s growing obsession with catching “Heisenberg” places his family and career at risk. When he discovers Walter’s identity, he confronts devastating truths about those closest to him.

His pursuit of justice comes at enormous personal cost. Hank’s fate underlines the unpredictability and powerlessness even upright characters experience amid systemic corruption and violent crime.

Saul Goodman’s Survival Instinct

Saul Goodman thrives on adaptability and self-preservation, counseling clients through legal manipulation and backhanded deals. Unlike other characters, he avoids deep remorse or attachment, choosing instead to prioritize his own safety above all else.

His involvement with Walter and Jesse often appears transactional. Saul’s comedic façade masks a sharp instinct for evaluating and escaping threats, whether from law enforcement or cartel enforcers.

By the end of the series, Saul’s instinct to go underground reflects his lack of illusion about the danger of his environment. Redemption is irrelevant to him; survival is the only metric that matters.

Gustavo Fring, Lydia, and The Cartel

Gustavo Fring operates with discipline, cunning, and secrecy. He builds a criminal empire by outmaneuvering both his Mexican cartel associates and law enforcement. Fring’s outward respectability stands in contrast to the ruthlessness he applies behind the scenes.

Lydia Rodarte-Quayle acts out of fear and pragmatism, managing supply lines and eliminating threats to secure her own future. Like Gustavo, her motivations are driven by risk management rather than remorse or innocence.

The Mexican cartel, represented by figures like Hector Salamanca and the Cousins, prioritizes loyalty and retribution. Power, not redemption, shapes their choices. None seek to change their fates; instead, they pursue dominance or survival until they are destroyed by rivals or law enforcement.

Character Motivation Key Traits Path to Redemption? Jesse Pinkman Guilt, atonement Regretful, loyal Struggles, never complete Hank Schrader Justice Persistent, honest Undermined by circumstances Saul Goodman Survival Cunning, detached Not a priority Gustavo Fring Power, control Ruthless, disciplined Never sought Lydia Self-preservation Anxious, practical Irrelevant The Cartel Loyalty, retribution Merciless, traditional Absent

Heisenberg’s Legacy and Cultural Impact

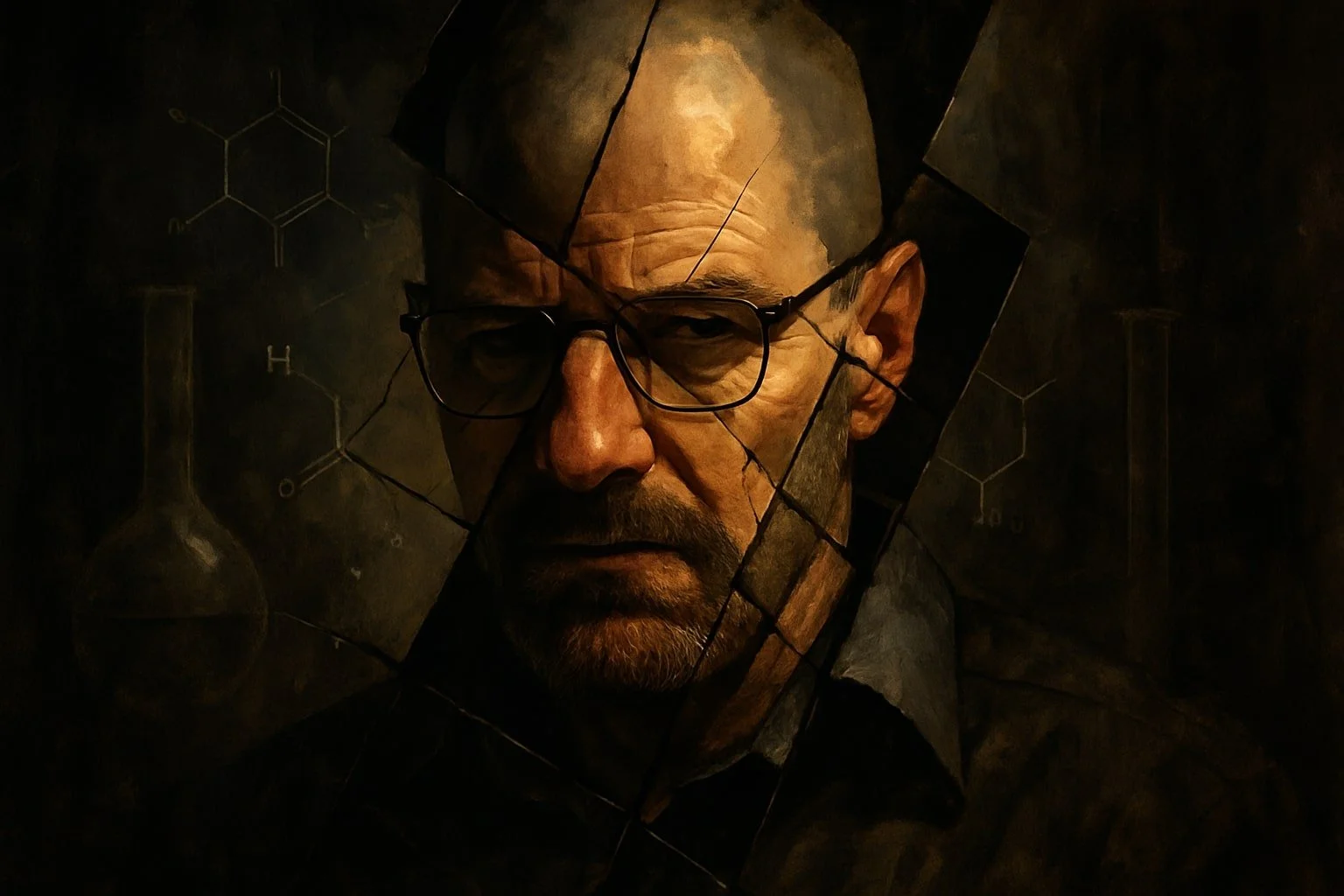

Heisenberg, Walter White’s alter ego, has left a lasting mark on television through striking imagery and narrative choices. The character’s impact continues to influence how audiences and critics view both crime dramas and antihero storytelling.

Iconic Symbols and Motifs

Breaking Bad’s use of symbols elevated it beyond standard crime dramas. The pink teddy bear, split in half and floating in Walter’s pool, foreshadowed disaster and suggested the moral and personal fallout of his actions. Its presence recurred across seasons, serving as a visual reminder of consequence.

Heisenberg’s black hat became shorthand for Walter’s transformation—from mild-mannered teacher to ruthless criminal. The ricin vial summarized his meticulous planning and willingness to kill covertly, representing his increasing moral decay. The machine gun, hidden in the trunk, marked the brutal final escalation of his story.

Cultural echoes appear in fan art, parodies, and comparisons to figures like Tony Soprano and Scarface. Each symbol ties Walter’s story to broader themes of ambition, guilt, and destruction, making these motifs deeply recognizable in modern television.

Critical Reception and Reviews

Critics consistently praised Breaking Bad for its writing and Bryan Cranston’s performance as both Walter White and Heisenberg. Reviewers highlighted the show’s refusal to offer easy redemption for its main character, setting it apart from contemporaries like The Sopranos and even classic tales like Scarface.

Many reviews noted the series’ dedication to realism and consequence. The slow unraveling from chemistry teacher to criminal icon drew both acclaim and debate, especially regarding the ethics of rooting for Heisenberg. Cranston’s portrayal received multiple Emmys and set new standards for antihero performances.

This complex legacy ensured that Breaking Bad would be compared to other groundbreaking shows, often cited as a major influence on modern television drama.

Final Judgment: Breaking Bad’s Refusal of Redemption

Walter White’s story concludes with a display of control and self-determination rather than traditional redemption. The series crafts an ending where moral accounting and personal consequence come to the forefront, deliberately avoiding a straightforward path to forgiveness.

Death on His Own Terms

Walter rejects the classic path of repentance and transformation at the end of his journey. Instead of seeking forgiveness, he meticulously orchestrates the final act that ends with his own death at the site of his last crime.

He uses his scientific skills—tools that first led him down his criminal path—to eliminate his enemies and free Jesse Pinkman. This act is not selfless; it serves his own sense of justice and unfinished business. Walt’s fate is not dictated by outside forces, but rather by his own decisions, illustrating his final claim over his life and legacy.

His death is a result of a wound sustained in the crossfire he initiated. Walt chooses his place and moment of death, compelling viewers to confront whether autonomy in one’s end is a form of judgment or an escape from it.

Aftermath and Moral Resonance

Breaking Bad does not offer a clear path to redemption or moral closure. Walt’s actions leave behind shattered families, ruined lives, and deep ethical questions about responsibility and consequence.

The show’s creators intentionally avoid cleaning up Walter’s legacy or offering redemption. Instead, the consequences for every character, including Jesse’s ambiguous future and Skyler’s hardship, highlight the lasting impact of Walt’s choices.

Viewers are left to weigh Walter’s final actions—rescue and revenge—against the scope of his harm. The lack of redemption is a deliberate choice, forcing an honest engagement with the consequences of crime and the limits of personal judgment.