How Yellowstone Turned the Fence Line into a Battlefield

Examining Conservation Conflicts and Land Use Challenges

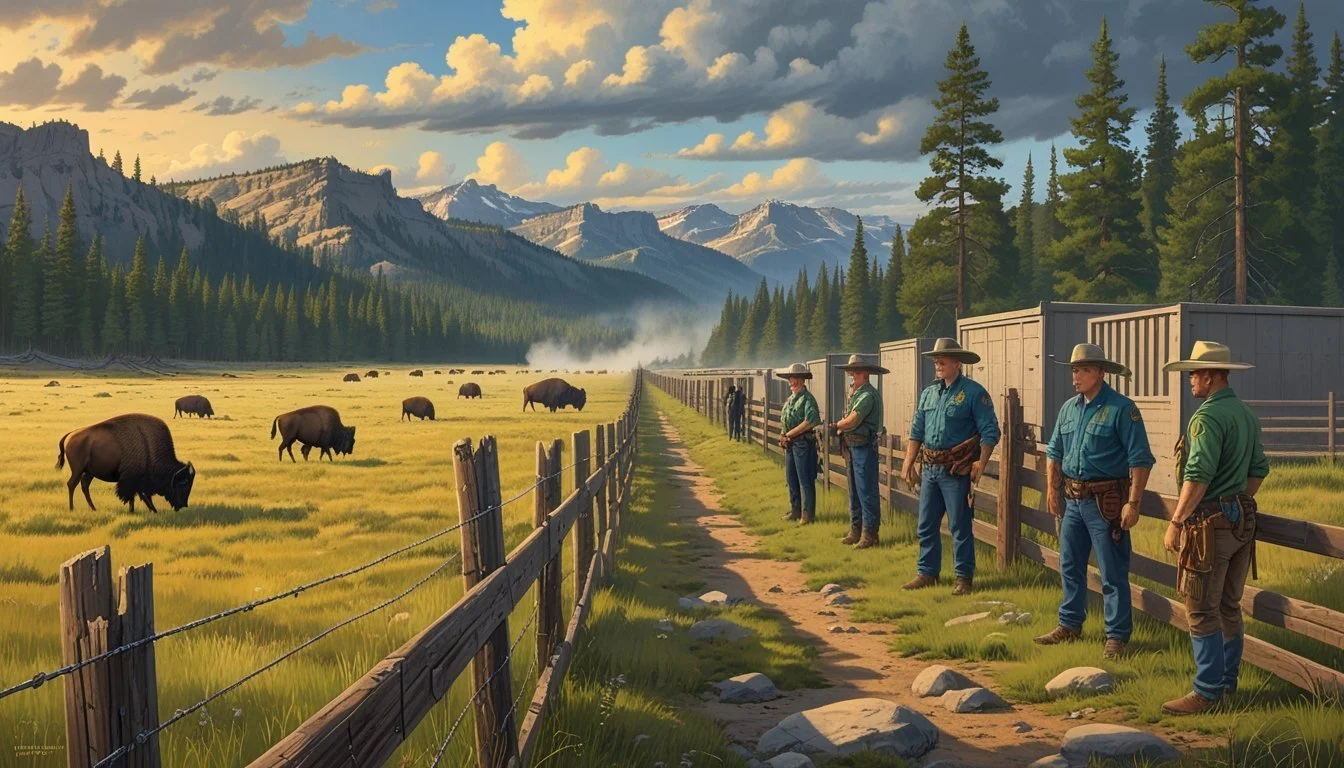

Yellowstone’s fence lines have long served as more than just physical barriers—they have become symbols of deeper conflicts over land, history, and identity. The land surrounding Yellowstone tells a story of shifting borders, ongoing disputes, and the legacy of both Native peoples and settlers who once called the region home. Fence lines, once meant to separate properties, have often turned into contention zones, mirroring past struggles like the Indian Wars and the infamous confrontations that occurred in areas such as the Little Bighorn Valley.

Disagreements over grazing rights, access, and conservation continue to define the Yellowstone region. Scenes like those depicted in television and real-world disputes over fences highlight how these boundaries both reflect and magnify long-standing tensions. Yellowstone’s landscape, shaped by history, law, and personal stakes, is a reminder that the battle over rights and resources persists at the very edge of America’s first national park.

Historical Background of the Yellowstone Fence Line

The Yellowstone fence line has a complex past, shaped by competing interests in land use, conservation policies, and the forces of expansion in the American West. Its history reveals how boundaries, both physical and political, became points of tension and negotiation.

The Origin of the Fence Line

Early boundary lines around Yellowstone were initially informal, guided by natural landmarks and local consensus rather than surveyed lines.

With the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the need for clear demarcation grew. The government introduced fence lines to protect park resources and restrict grazing and unauthorized entry. These boundaries represented the shift from open land to regulated territory.

Conflicts quickly emerged between federal authorities and local ranchers. The fence line altered grazing patterns and disrupted established routes. Ranchers, who depended on seasonal migration, found their traditional practices limited by these newly enforced barriers.

Disputes often led to damaged fences and legal confrontations. The fence came to symbolize federal control over land use in the region.

Yellowstone National Park and Territorial Boundaries

Yellowstone National Park spans three states: Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. When Congress created the park, precise territorial boundaries had not been established, leading to jurisdictional confusion.

Initial surveys struggled with the region’s rugged terrain. This resulted in shifting and sometimes disputed lines, affecting law enforcement and land management. Over time, official surveys clarified boundaries, but inconsistencies lingered for decades.

These park borders influenced who had authority over the land. Federal regulations sometimes conflicted with state interests, especially regarding resource use and local governance. The boundaries did not always align with natural features, leading to further complications for those living near the park.

Railroad Expansion and Land Use

Railroad companies began to move into the Yellowstone region in the late nineteenth century. Their arrival accelerated settlement and increased pressure on the park’s perimeters.

Railways offered easier access for tourists but also facilitated livestock drives and timber extraction. Companies often negotiated for land adjoining the park, sometimes seeking to extend tracks within the boundaries.

The railroad’s presence changed land use patterns and intensified confrontations over resources. Competition for land along the fence line increased, as ranchers, speculators, and the federal government all aimed to control access and development.

Railroad expansion made the fate of the fence line a central issue, connecting national park policies to broader economic development in the country.

From Barrier to Battlefield: The Changing Role of the Fence Line

As settlement advanced through the lands that would become Yellowstone, fence lines shifted from practical boundaries to sites of open conflict. These fences influenced property disputes, military decisions, and travel routes along contested trails such as the Bozeman Trail.

Conflict Between Settlers and Indigenous Nations

Fence lines erected by settlers often marked more than property—they signaled permanent occupation of land long used by Indigenous nations. The arrival of homesteaders led to the enclosure of hunting grounds and sacred sites.

This generated frequent confrontations, with many disputes centered on access to resources like water and grazing areas. Fences, intended to keep livestock in or out, became flashpoints for violence, especially in regions near Fort Smith and along the Bozeman Trail.

Indigenous resistance sometimes involved dismantling fences or moving stock across boundaries. Settlers reported fears of raids, while Native leaders viewed fences as threats to their survival and autonomy.

Military Strategy and Tactical Uses

During the Indian Wars, fence lines became part of the larger battlefield landscape. Commanders at forts such as Fort Smith leveraged fences and natural barriers in their defensive plans.

Infantrymen and cavalry units used existing fences for cover or as obstacles to slow enemy advances. Makeshift entrenchments, combining earthworks and fence rails, offered protection during skirmishes. The military quickly learned to repurpose these civilian structures for tactical advantage, particularly when outnumbered or caught in unfamiliar terrain.

Fences, walls, and improvised barricades provided observation points and first lines of defense, giving soldiers a crucial edge in open-country engagements.

Bozeman Trail Crossings

The Bozeman Trail cut across tribal lands, and its intersections with fence lines became sites of repeated contention. Settlers and military escorts faced persistent attacks when crossing fenced boundaries, prompting both sides to fortify or destroy these markers as needed.

Some crossings were fortified with extra fencing to funnel travelers, while others were deliberately left open to avoid provoking additional hostilities. Tension escalated at pinch points where trails, fences, and military escort routes converged, often near key locations such as Fort Smith.

Records from the period show a cycle of building and destruction, where each new fence or barrier represented not only a claim to land but also a potential spark for battle.

Key Battles and Figures Along the Fence Line

Violent clashes over land and sovereignty shaped the region’s history, with key confrontations and notable leaders marking the conflict. These battles often took place along contested territory lines that came to represent much more than simple property boundaries.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, fought on June 25–26, 1876, stands as a significant and well-known clash between the 7th Cavalry led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and a coalition of Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. Outnumbered and outmaneuvered, Custer's force was surrounded and decisively defeated.

The battlefield, now the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, is marked by white marble and red granite memorials showing where soldiers and warriors fell. The fight’s outcome directly challenged U.S. military campaigns and policies in the northern Plains. The Little Bighorn became symbolic of Native resistance and highlighted the critical role of leadership and tactical unity.

Rosebud and Powder River Skirmishes

The Rosebud and Powder River skirmishes were pivotal in the lead-up to Little Bighorn. On June 17, 1876, General George Crook’s troops encountered a large force of Lakota and Cheyenne under Crazy Horse along Rosebud Creek. In what became known as the Battle of the Rosebud, Crook’s men were forced to retreat, missing a crucial opportunity to unite with Custer.

Earlier in 1876, the U.S. Army launched the Powder River Expedition to attack winter villages. These confrontations strained resources and heightened mistrust on both sides. The battles at Rosebud and Powder River exposed weaknesses in U.S. coordination while emboldening Native leaders and their followers.

General Crook and Custer’s Campaigns

General Crook and Lieutenant Colonel Custer played central roles in executing the U.S. military strategy against the Sioux and Cheyenne. Crook’s campaign aimed to threaten Native encampments along key waterways and cut off routes of escape or resupply. Both men faced significant logistical and intelligence challenges during the campaign season.

Custer’s aggressive tactics at Little Bighorn cost him his command and dramatically altered public opinion. Crook's setback at Rosebud limited the army’s effectiveness and highlighted communication failures in a complex military environment. Their actions and miscalculations had long-standing effects on subsequent campaigns and treaties in the region.

Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Two Moon

Sitting Bull, a respected spiritual and political leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota, inspired resistance and played a critical role in mobilizing allied forces. His strategic insight and ability to forge alliances among Sioux and Cheyenne bands were instrumental. Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota war leader, commanded respect for his valor and tactical skill, coordinating key movements in both Rosebud and Little Bighorn.

Two Moon, a prominent Northern Cheyenne chief, provided leadership during Little Bighorn and shared first-hand accounts of the battle. These leaders exemplified unity and resistance, enabling their people to withstand superior firepower and numbers. Their legacies are intertwined with the battle-scarred landscapes that once marked disputed fence lines and boundaries.

Impacts on Communities and the Landscape

Persistent disputes over land use and access in the Yellowstone region have led to significant changes for local communities and the broader landscape. These effects can be traced to cultural tensions, shifting management practices, and ongoing debates about property, tradition, and stewardship.

Crow Agency and Local Populations

The boundaries of Yellowstone have affected the Crow Agency and other Indigenous groups, whose ancestral territories once covered parts of the park region. Federal land designations restricted traditional hunting, fishing, and access routes, forcing families to adapt to new economic realities.

For many, these changes have resulted in a loss of cultural practices and increased tension with authorities. Tall fences and closed borders symbolized exclusion, pushing some to advocate for restored rights and recognition.

The impact extends into community relationships, as disputes over land rights continue to influence trust and cooperation between local governments and tribal councils. Issues of sovereignty and representation remain central, with many residents seeking solutions that respect both tradition and modern pressures.

Effects on Farming and Land Management

Ranchers and farmers near Yellowstone often face conflicts due to changing park boundaries and policies. Restrictions on grazing, wildlife migration, and land use have forced many to alter traditional practices or invest in new fencing and permits.

Wildlife migration patterns directly affect livestock, particularly when bison or elk cross between protected areas and private property. This creates economic challenges and sparks legal battles over compensation and responsibility.

Some landowners have adapted by integrating conservation principles into their operations, while others advocate for policy changes to better protect agricultural interests. The struggle to balance production with preservation continues to shape the region’s approach to land management, with long-term consequences for future generations.

Preservation of Yellowstone Battlefields

Yellowstone's battlefields, both literal and metaphorical, have required careful oversight to ensure their legacy endures. Preservation has involved a complex interplay between legislation, federal agencies, conservation design, and the demands of tourism.

Conservation Efforts and Design Proposals

Efforts to conserve key sites in Yellowstone have included a mix of physical restoration, restricted access zones, and interpretive infrastructure. Earthworks and fortifications, remnants of Army patrols and ranger barricades, have sometimes been stabilized using reinforced materials to prevent erosion.

Design proposals often sought to balance visitor engagement with habitat protection. For example, boundary fencing—once symbols of exclusion or military presence—were reimagined as tools for safeguarding fragile areas. Erosion controls, signage, and walking paths were common solutions proposed in preservation plans.

The Bureau of Mines and Geology contributed by assessing potential hazards from old infrastructure. Their assessments have informed where restoration work should be prioritized to preserve both historical artifacts and natural processes.

Role of Congress and Government Agencies

The U.S. Congress played a central role in Yellowstone’s early preservation, starting with the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act of 1872. This act established the park as the first of its kind, setting aside land for public benefit and scientific inquiry.

Subsequent congressional action ensured that preservation was codified in law, empowering agencies to enforce regulations and protect critical sites. The National Park Service and allied agencies—including the U.S. Army during the late 19th and early 20th centuries—implemented these policies.

Regular oversight ensured that preservation projects received adequate funding and staffing. These efforts also influenced how hotels and tourist amenities were managed, making sure their development did not harm historic areas.

National Significance and Tourism

Yellowstone’s preserved battlefields and historic fence lines are a major draw for visitors interested in history and conservation. Sites of former military installations still feature interpretive plaques and guided walks, helping guests understand the park’s complex past.

Tourism contributes to funding continued preservation, with entrance fees and hotel taxes sometimes earmarked for restoration projects. Educational programs highlight how preservation efforts benefit both the park and future generations.

The park’s national significance is often emphasized in visitor materials, connecting local preservation with broader themes in American history. These interpretive efforts reinforce the importance of responsible stewardship in the face of ongoing environmental and social pressures.

Yellowstone’s Place in the Broader Context of American Battlefields

Yellowstone’s history is deeply entwined with moments of conflict, political tension, and cultural transformation. Its story connects to both military battlefields and the ongoing struggles over land, resources, and national identity in the United States.

Comparisons to Gettysburg and the Civil War

Gettysburg stands as a symbol of military confrontation and the struggle over the nation’s direction during the Civil War. Yellowstone, though not a site of armed conflict like Gettysburg, has served as a battleground for clashes over conservation, land use, and federal authority.

The debates surrounding Yellowstone’s management echo the ideological divides evident in the Civil War—federal power versus local or private interests. Just as Gettysburg became a site for examining national values, Yellowstone’s policy battles reflect shifting concepts of what should be preserved and who gets to decide.

While Gettysburg’s legacy rests on its explicit violence and aftermath, Yellowstone’s battlefield has been defined by legislative campaigns, protest movements, and environmental policy shifts. Both sites underscore how American landscapes can become stages for larger cultural and political struggles.

Big Hole National Battlefield and the Nez Perce

The Big Hole National Battlefield in Montana commemorates a violent encounter between the U.S. Army and the Nez Perce people in 1877. This confrontation was part of a larger campaign forcing Native Americans from their lands.

Yellowstone shares a connected history. When the park was established, Indigenous groups were barred from ancestral territories, often under threat. The Nez Perce’s journey through Yellowstone during their flight highlights these overlapping histories of exclusion and conflict.

Both places represent more than singular events—they illustrate the broader pattern of Indigenous displacement and resistance. The physical boundary lines mapped in these areas became stark symbols of contested authority and cultural survival.

Railroads: The Illinois Central Railroad in the American West

The expansion of railroads such as the Illinois Central Railroad shaped access to the American West and influenced how landscapes like Yellowstone were perceived and used. While the Illinois Central primarily connected the Midwest to the South, its model of corporate influence and land lobbying was mirrored by other lines reaching the West.

Railroad companies pushed for tourism development within Yellowstone, directly shaping policies on land use and federal management. This corporate expansion became a point of contention analogous to the disputes over national battlefields, where economic interests often clashed with preservationist goals.

The arrival of the railroad marked a shift from military conquest to economic penetration, turning natural wonders like Yellowstone into battlegrounds of a different sort—where commerce, conservation, and national identity were all at stake.